LLMs excel at book learning, but humanity is running out of text to train on. As Ilya Sutskevar put it, “we have but one internet.”

For AI in medicine, the next step is physiological ground truth. The gold standard in medicine is a blood test, typically measured every few months or years. Consumer wearables (Apple Watch, Samsung Galaxy, Fitbit) have health sensors that measure information daily, and are increasingly becoming medical devices (Apple Watch has five FDA clearances).

At the NeurIPS workshop on timeseries for health, we presented work on training a health foundation model using a data set of both wearables and blood-based biomarkers. Our approach was inspired by JEPA and world models.

JETS: a health foundation model based on JEPA

JETS (joint embedding for timeseries) is a foundation model pre-trained on 3 million de-identified person-days of wearable data. JETS was evaluated on downstream medical tasks such as disease prediction and biomarker prediction.

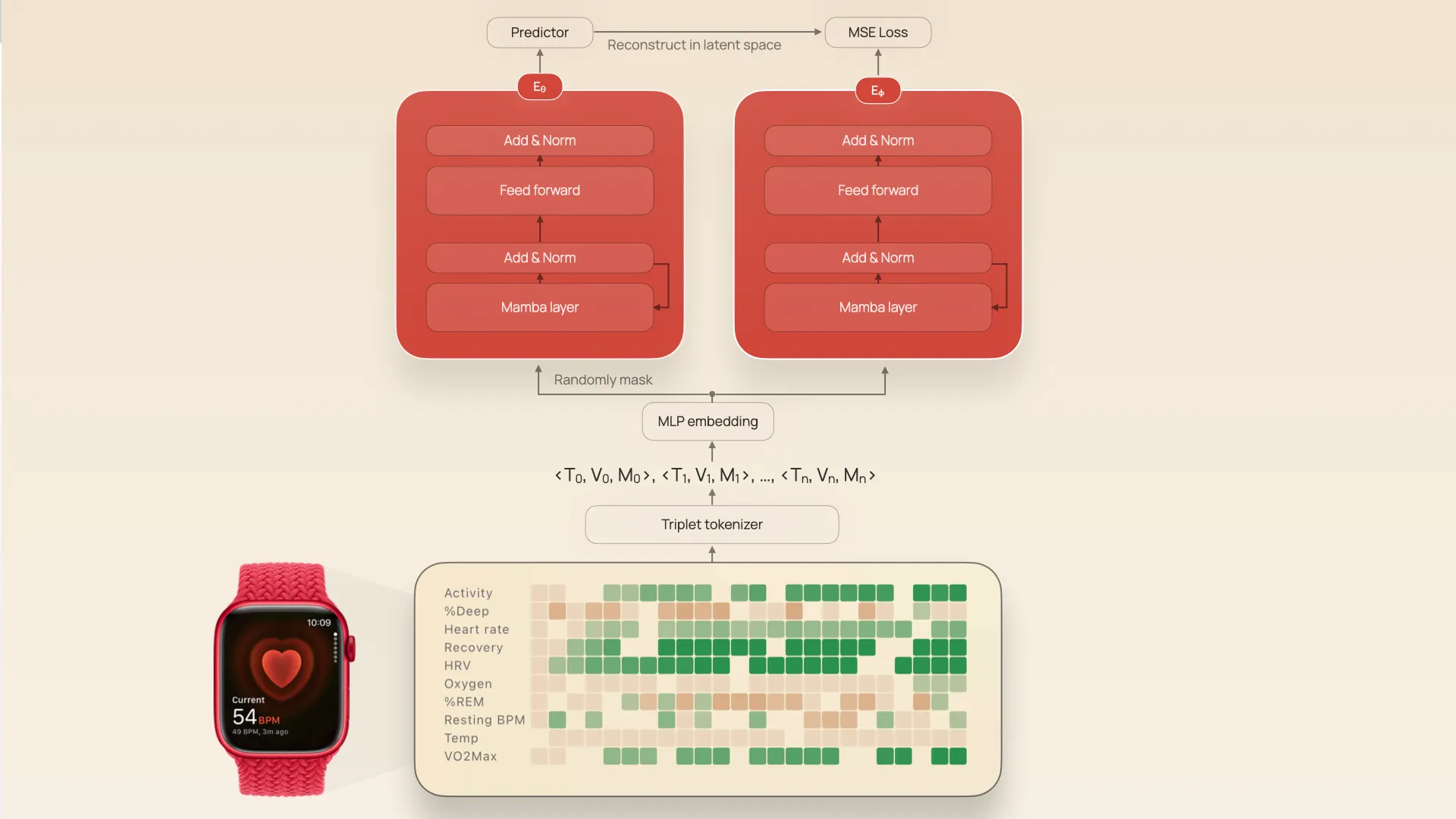

The input is an irregularly-sampled multivariate timeseries (IMTS) with 63 channels: things like oxygen saturation, resting heart rate, sleep stages, and so on. The raw IMTS are represented as triplets (t[i], v[i], m[i]) corresponding to the timestamp, metric value, and metric type. These triplets are then converted into a stream of tokens with a hidden dimension d=64.

Architecture of JETS, showing tokenization and joint embedding encoders

Architecture of JETS, showing tokenization and joint embedding encoders

The stream of tokens are then used as inputs into two twin encoders, Eθ and Eϕ. Eϕ sees the whole token sequence, Eθ sees a random 30% of the sequence, and both networks have tied weights (the weights of Eϕ are set as an exponential moving average of Eθ, which has been shown to prevent representation collapse). The networks are trained to ultimately map both masked and unmasked token sequences into the same latent space by also training a predictor $P$ that predicts the latent vector of Eϕ given the output Eθ and positional embeddings of the masking.

JETS is a JEPA (joint embedding predictive architecture) adapted to timeseries. JEPA’s are an alternative to things like masked autoencoders. Whereas a masked autoencoder is trained to reconstruct the raw input signal through a low dimensional latent “bottleneck”, JEPAs are trained to reconstruct in latent space instead. This allows the encoder to only focus on meaningful distinctions, rather than having to exactly reproduce the details of the input data.

We tried variations of JETS with both Mamba and Transformer blocks.

To test whether this pre-training process produced meaningful latent space, we evaluated it on two tasks: predicting diagnoses and predicting biomarker values. (Both tasks were evaluated using linear probing, i.e., fine-tuning only weights of the last layer while keeping the rest of the network frozen).

Results

JETS had high accuracy at detecting hypertension (87% AUROC), atrial flutter (70%), ME/CFS (81%), and sick sinus syndrome (87%). In particular, JETS was more accurate than baselines like Masked Autoencoders and PrimeNet.

When it came to predicting absolute levels of biomarkers, JETS (or its transformer analogue) had higher accuracy than baselines at predicting HbA1c, glucose, HDL, and hs-CRP (inflammation), although all models have high absolute error. I think an interesting future direction would be to try to predict a change in these biomarkers given a baseline measurement and wearable data since the baseline measuremrent.

Our contributions

JETS isn’t the first wearable foundation model: it builds on prior research such as DeepHeart (2018); Google’s LSM-1 (2024), LSM-2 (2025), and SensorLM (2025), and Apple’s PPG/ECG model (2024) and wearable behavioral model (2025).

But we think we’re making three important contributions.

Contribution 1: Little tech can win in AI

First, JETS shows that a tiny startup—Empirical Health is three people—can do work in the league of the big labs. For example, the data scale of JETS is actually comparable to work published by Google and Apple:

| Model | Institution | Data Scale |

|---|---|---|

| DeepHeart | Cardiogram/UCSF | 400,000 person-days |

| LSM-2 | 2 million person-days | |

| SensorLM | 3 million person-days | |

| Apple wearable | Apple | 19.8 million PPG samples / 3 million ECGs |

| Apple behavioral | Apple | 278,000 participants |

| JETS | Empirical Health | 3 million person-days |

When it comes to results, we actually report a higher accuracy at detecitng hypertension (87%) than some previous work reported by larger labs (with the obvious caveat that all of these papers are reporting results on different data sets).

It’s a myth that you need billions of dollars and hundreds of researchers to advance AI. Small labs — startups and academic labs — can make state of the art machine learning contributions, push the field forward, and even save lives.

Contribution 2: Adapting JEPA to multivariate timeseries with irregular sampling

Second, we make some specific technical contributions. Previous attempts to train JEPA models on timeseries (such as TS-JEPA) handled univariate timeseries; we extend this to multivariate, irregularly sampled timeseries. Several previous wearable foundation models trained on short, regularly-sampled snippets (e.g., a 30-second PPG); JETS handles long-range, multimodal, irregularly-sampled behavioral timeseries.

Contribution 3: AI beyond LLMs

LLMS have been wildly successful, but we’re out of text to train on. There’s no second internet.

If we’re to achieve health superintelligence, we need to figure out how to train on physiological ground truth. Computer vision is one obvious area with video ground truth (for physical world models), but timeseries are ubiqutous in healthcare. We think JEPA architectures and world models are a promising direction that’s underexplored.

Conclusions

This work is obviously just a first step in a broader vision, but we’re excited to share this small milestone. Much work remains: trying out contrastive losses, alternative tokenization strategies, analysis of bias and fairness, and, of course, deployment of these foundation models: either independently (as done here), as a proxy reward in reinforcement learning (i.e. to tighten the feedback loop mentioned in the opening), or aligned to the latent space of an LLM (as done in CLIP). If you’re a machine learning engineer or researcher interested in contributing to the future of health, please get in touch!

Get your free 30-day heart health guide

Evidence-based steps to optimize your heart health.